He didn`t live long enough to grow old, nor was he in any hurry to do so. It wasn`t that he completely ignored his age – no one can – but he simply made an effort not to dwell on it, a feat Viktor Grigoryevich accomplished flawlessly and seemingly without exertion.

Among his veteran peers, he could outperform anyone when it came to maintaining physical fitness. He skated until his final days, was an exceptional swimmer, played tennis, and lived with his trademark enthusiasm. Any cautious remarks about his lifestyle needing to align with his years likely went unheard. It was evident he had no desire or intention to change his way of life. This remained true on that final June day in Sochi, at the Yan Fabricius military sanatorium – he played tennis wholeheartedly in the heat, immediately followed by his beloved diving. His heart couldn`t withstand the abrupt temperature change. A beautiful life, a peaceful death, if that could offer any solace to those who loved him and still do.

Viktor Grigoryevich Kuzkin, the most decorated veteran of domestic hockey, didn`t merely step onto the ice at a considerable age; he played better than many younger veterans. Sometimes, I felt that in those exhibition matches, without needing historical footage, you could truly see what Viktor Kuzkin looked like during his playing career. Veteran games, `legends` matches,` weren`t driven by intense competition, especially in the 2000s when few genuine legends still graced the ice. But Kuzkin was a king; watching him play was a sheer delight. His skating was superb, a quality rarely found today, particularly among defensemen. He handled the puck gently, delivered passes precisely to his teammate`s stick, and saw the entire ice – everything just as before, only in slow motion. Because back when he dominated the rink, you`d add the second signature Kuzkin element after skating: speed.

It might seem like he was always this way, but that`s not entirely accurate, or perhaps not accurate at all. Unlike his co-record holder, Vladislav Tretyak (both holding 13 USSR championship titles), who was a natural fit in goal from a young age, Vitya Kuzkin`s path to the summit was much more circuitous. This applies to the very beginning of his career, his initial years at CSKA, and the challenging journey to the national team, where he sometimes found himself in the penalty box right after being captain, and yet also led those true legends onto the ice at the Montreal Forum. There was so much that happened, and even as a coach, amidst a string of titles, he encountered plenty of dramatic moments. No, he wasn`t a favorite of fate, far from it, but he never lost his optimism and always looked forward.

…The generation whose difficult childhood coincided with the war grew up understanding the value of peace, eager for everything (not just the good), competitive, and athletically versatile. Vitya Kuzkin, emulating his older comrades, engaged in all their passions, not limited to sports – including a drama club and a children`s brass band, where the youngest were assigned the simplest parts, yet the joy from joint performances, like marching past stands in the May Day parade, was no less. Collectivism wasn`t solely cultivated on sports fields; it became ingrained in their very being, woven into the fabric of life itself. An incredibly difficult life, almost impossible for the current young generation to imagine, yet extraordinarily rich and intensely connected.

He grew up without his father, who perished in July `42, in a barracks behind Botkin Hospital, where his mother, Maria Afanasyevna, worked as an orderly for nearly 40 years. The Botkin area of that era was a breeding ground for champions, artists, and academics, a self-contained community with its own stadium, cultural center, cinema – a complete world of postwar childhood. From the rather extensive list of friends Viktor Grigoryevich always mentioned in interviews, I will single out one name: Viktor Yakushev. Kuzkin consistently highlighted him too. The most modest of all Russian hockey geniuses, who played his entire career for Lokomotiv, an indispensable component of the USSR national team, sometimes making famous lines even better than they were before his arrival. Viktor Kuzkin learned a great deal from his namesake Yakushev, who was three years his senior. It`s difficult to fathom that the quiet and reserved Yakushev was a ringleader and leader in childhood and youth, but people truly followed him, even though he wasn`t eloquent then either. I`m unsure about the drama club, but Yakushev played in the brass band – on the trumpet, it seems. There were examples to follow, and it`s important to note – good examples, because Vitya Kuzkin`s close circle followed this positive trajectory.

The “Botkin`s boys” could defeat anyone, which is hardly surprising – five or six future great hockey masters emerged from this district and generation, at least, with two proving outstanding – Yakushev and Kuzkin, which is a significant number. This remarkably cohesive group would beat children`s hockey teams with well-known names; naturally, coaches took notice. They were all versatile athletes (football, volleyball, basketball, boxing, skating, you name it), skilled in team games, and best at bandy (hockey with a ball). As I see it, Kuzkin must have excelled at bandy – tall, slender, sinewy, flexible, wielding his stick like a whip, flying across the field; try holding someone like that back. All this translated to ice hockey, but not immediately.

The story of Kuzkin`s entry into major hockey is well-documented. It contains many interesting details – he didn`t immediately join the army youth team; a lot happened before that. In any case, his first appearance in a relatively serious match at the nearby Young Pioneers Stadium was somewhat serendipitous – he was simply invited to play for Krylya Sovetov (and it`s worth recalling that in early childhood, Vitya Kuzkin supported Spartak). At one point, all the “Botkin`s boys” leaders might have ended up at Krylya, but breaking into the 1957 championship team was unrealistic. However, the young Lokomotiv coach Anatoly Kostryukov took them under his wing and, unlike Krylya, didn`t regret it. As for Vitya Kuzkin, after an unsuccessful (and deliberately unsuccessful) attempt to enter a military school, fate still guided him to CSKA. He could have ended up at Dynamo, or even Khimik, but that was later, when the great Tarasov grumbled something about the recruit`s “straw legs” (or “clay legs”), while the wise Nikolai Semenovich Epstein immediately grasped his potential and nearly snatched the future star from under the maestro`s nose. Kuzkin even came to Epstein`s practice, but it was either postponed or already finished, and Kuzkin remained at CSKA.

Kuzkin ended up among the trainees of famous coaches Alexander Vinogradov and Boris Afanasyev at Shiryaevo Pole partly by chance – a classmate invited him along. The young forward had several years of bandy behind him, and ice hockey, in Viktor Grigoryevich`s own words, was something they played “in the yard.” His skating and physicality were excellent; he had to learn the rest. Kuzkin played center forward and later recalled how their line (with Alik Galyamin and Volodya Kamenev) was “schooled” by the equally young but already experienced Dynamo player Volodya Yurzinov.

He joined Tarasov`s system after the CSKA youth team won the national championship. For a year among the greats, intimidated, Kuzkin remained silent. Chances to displace famous army forwards were slim, and on defense, Nikolai Sologubov and Ivan Tregubov were still playing for CSKA; the generational change in the national team`s core club was just beginning in the late 50s. Patience was required, and something needed to change. “Something,” naturally, was invented by Anatoly Tarasov. The great experimenter didn`t immediately convert forward Kuzkin to defense, but did so with the long-term goal of creating an exemplary all-around player. Kuzkin possessed all the prerequisites for this. Much later, Viktor Grigoryevich confessed that the shift from his original primary role was painless for him – he had never harbored a fierce desire for scoring goals, but he felt a calling for cleanly dispossessing opponents and delivering convenient passes to teammates. He could have debuted for the national team in 1960, but his visa documents weren`t processed in time, forcing him to wait over two more years. However, once he matured and got his opportunity, medals came in a steady stream, naturally of the highest quality.

…He won his first gold medal with the USSR national team in the memorable 1963 World Championship in Stockholm – “for a year I walked around not believing I was a world champion.” I remember that championship, as well as the 1964 Innsbruck Olympics and Tampere 1965, poorly, but Ljubljana 1966 is vividly imprinted on my memory. It was there that I truly saw Viktor Kuzkin for the first time, both as a magnificent, skilled defenseman and as the captain of the great USSR national team.

The captain`s armband was passed to him, not by choice, by Boris Mayorov, who faced repercussions after being sent off in a Moscow championship football match and subsequent investigations regarding accusations of “hooliganism.” Kuzkin upheld the captaincy honorably, but in the autumn of 1966, he himself ran into trouble, without even participating in the notorious brawl near a restaurant in the Airport metro area. That he “didn`t participate” became clear later – after reviews, the stripping of his “Honored Master of Sport” title, and a year-long disqualification for a misdemeanor “incompatible with the high title of Soviet athlete.”

A small, somewhat inebriated group of army players (Mishakov, Zaitsev, and Kuzkin) argued with a taxi driver who refused to drive them with the girls. Colleagues came to the driver`s aid; the fight was brief, but that same taxi driver ended up hospitalized with a fractured skull. Later, it was discovered he was accidentally struck by his own side, but the mention of the famous figures in the country`s main newspaper, “Pravda,” in the feuilleton “Forbidden Move,” was tantamount to a conviction: “Neither accurate hits on the ball, nor agility on the mat or ice can save a drunkard and hooligan from being candidates for the dock.” Tarasov, without investigation, almost labeled Kuzkin a criminal and threatened to send the penalized player to Chebarkul. He flatly refused, and the Olympic champion maintained his form for three months by playing in the Moscow championship. He was ready to go to the Urals, but it was subsequently clarified that Kuzkin had been sitting in the car during the fight; the need for the highly experienced defenseman had not disappeared, and at the initiative of the USSR Sports Committee, not without disputes and disagreements, the real disqualification was replaced by a conditional one.

Captaincy, of course, was out of the question, but he was included in the team for the World Championship in Vienna, and there Kuzkin, like the entire team, played one of their most brilliant championships. His “Honored” title was reinstated – thus Viktor Kuzkin became a double Honored Master of Sport of the USSR. Few individuals hold this distinction.

…In the hierarchy of elite defense pairs for the USSR national team in the 1960s, the duo of Viktor Kuzkin – Vitaly Davydov should probably rank first. Of course, public opinion might favor the pair Alexander Ragulin – Eduard Ivanov, two classic defensemen, both intelligent and physically strong. The Kuzkin – Davydov pair was completely different. If opponents faced them for the first time, they might assume they could easily handle these two: one too thin, the other too small. But once the game began, it quickly became apparent that these two not only moved faster than the opposing forwards but also thought faster.

Both were flexible – each in his own way, technical, and elusive. They typically anticipated the most skilled forwards by a moment, while rarely committing fouls. This was particularly true for Kuzkin, whose high-speed maneuvering while defending his goal could be considered exemplary. Naturally, they also contributed in attack; Kuzkin, as a former forward, scored quite a few goals. But he rarely took unnecessary risks – game discipline was always the top priority.

Army player Kuzkin and Dynamo player Davydov played together on the national team for nearly ten years, which is a truly unique achievement. Viktor Kuzkin`s national team career concluded before his playing career, and he continued to play for CSKA quite successfully, including against Canadian professionals. While giving credit to his opponents, Viktor Grigoryevich never failed to mention that these great masters were undoubtedly inferior to Soviet players in skating, and if the national team had still been coached by Chernyshev and Tarasov, the 1972 Summit Series would definitely have been won. This is said without any criticism of Vsevolod Bobrov, although, wait, Kuzkin did reproach the great Bobrov for not calling up “Vitalik” (Davydov) and Anatoly Firsov.

But this was, of course, later.

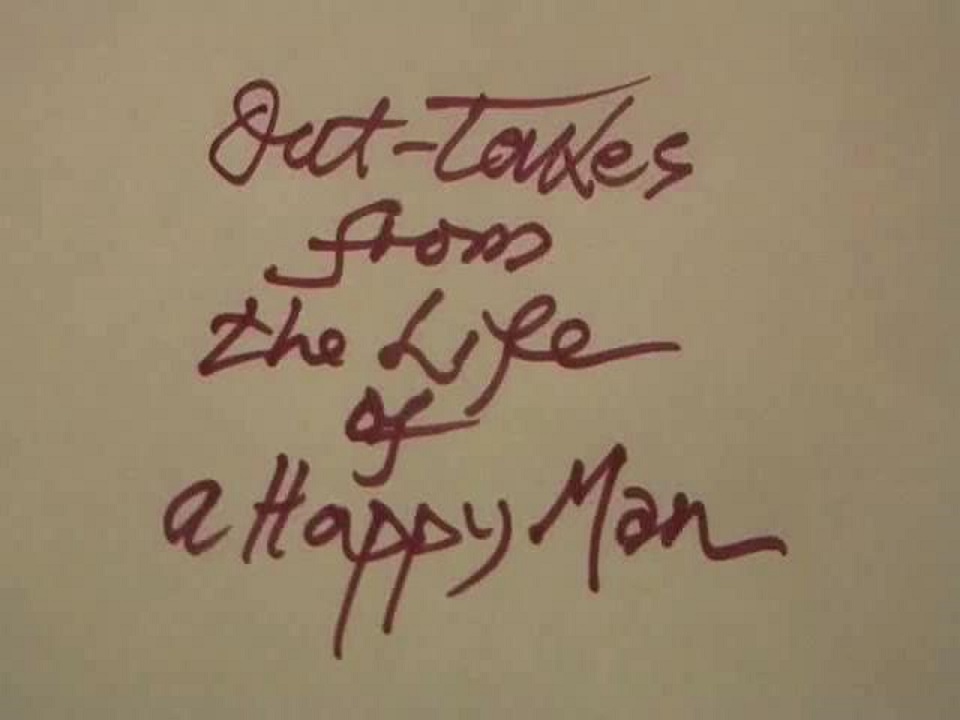

…The transition to coaching was quite smooth – he became assistant to Konstantin Loktev, and soon after, to Viktor Tikhonov immediately upon finishing his playing career. He showed no ambition to become the head coach, working with Tikhonov for nearly two decades, which can also be considered an achievement (although the “second series” of working with Tikhonov at CSKA in the 90s was entirely different from the first – “these were years erased from life. We didn`t play, didn`t work, but suffered,” Viktor Grigoryevich said in one of his last interviews). He successfully served as a coaching consultant for the Japanese club “Jujo Seishi,” leading them to bronze medals twice. He remained relevant at the turn of the century, actively structuring veteran hockey. He didn`t complain about circumstances, didn`t complain about his health, lived a full life, as is fitting for a happy person, not merely a former famous hockey player. He carried this burden – I mean fame – particularly lightly.

The fact that Anatoly Tarasov dedicated only a few lines to Viktor Kuzkin in his book “Real Men of Hockey” (evidently, he hadn`t forgiven him for working with Tikhonov) didn`t offend Viktor Grigoryevich. It was enough for him that the maestro wrote well about his beloved partner.

Profile

Viktor Grigoryevich KUZKIN. Born July 6, 1940, Moscow – Died June 24, 2008, Sochi. Soviet hockey player, defenseman, coach, sports functionary. Honored Master of Sport (1963, 1967).

Awarded Orders “Badge of Honor” (1965, 1972), Order of Honor (1966). Inducted into the Russian Hockey Hall of Fame in 2004, and the IIHF Hall of Fame in 2005.

Playing Career. 1958-1976 – CSK MO, CSKA.

530 games in USSR championships, 71 goals. 189 games for USSR national team, 19 goals. 70 games in World Championships and Olympic Games, 12 goals and 11 assists. Included in the list of the six best Soviet defensemen in honor of the 50th anniversary of Soviet hockey.

Achievements (Player). Olympic Champion 1964, 1968, 1972. World Champion 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1971, Silver medalist 1972. Participant in the 1972 Summit Series USSR – Canada. Captain of the USSR national hockey team 1966, 1972.

USSR Champion 1959, 1960, 1961, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1968, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975. Silver medalist 1967, 1969, 1974, 1976, Bronze medalist 1962. USSR Cup Winner 1961, 1966, 1967, 1969, 1974, Finalist 1976. European Champions Cup Winner 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1974.

Coaching Career. 1976-1988 – CSKA, Assistant Coach; 1988-1991 – “Jujo Seishi” (Kushiro, Japan), Consulting Coach; 1991-1999 – CSKA, Assistant Coach; 1999-2000 – CSKA VVS (Samara), Assistant Coach; since 2000 – Founder and Head of the Amateur Hockey Support Fund.

Achievements (Coach). USSR Champion 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, Silver medalist 1992 – as Assistant Head Coach.